Traversing the “Crouching Tiger” of Gubeikou

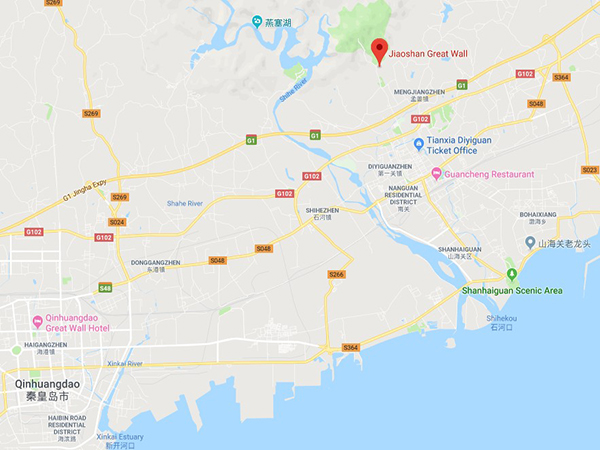

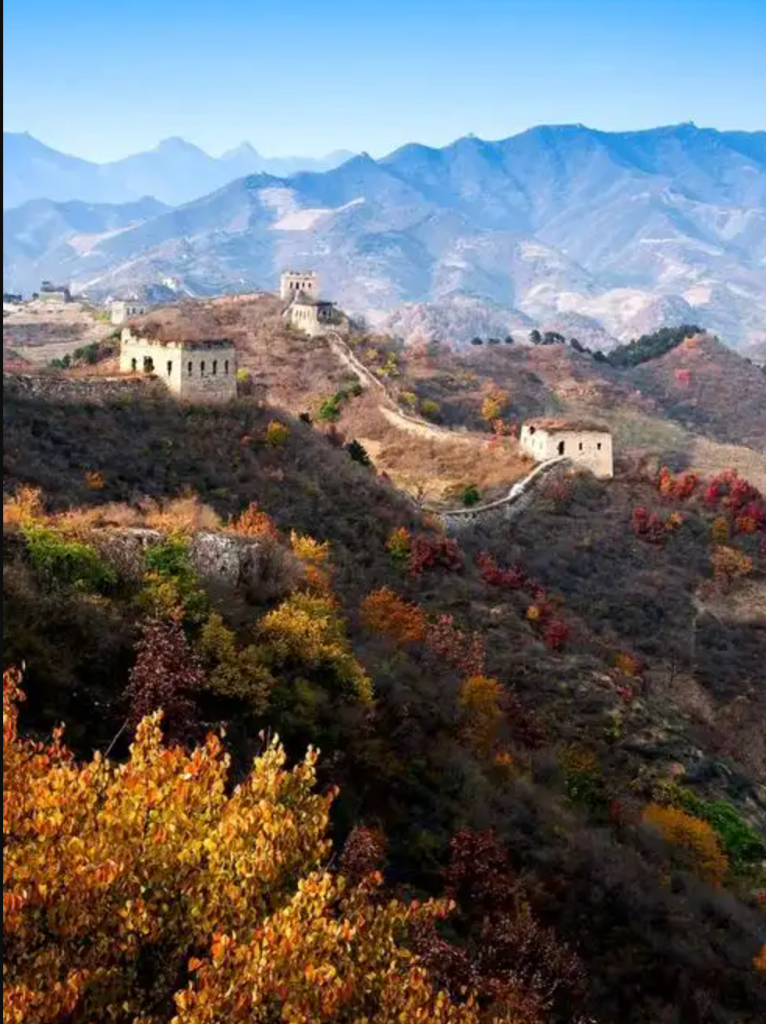

Nestled in the western part of the Gubeikou Great Wall System, Wohushan Great Wall (literally “Crouching Tiger Mountain Great Wall”) is a raw, unrenovated section that lives up to its name. Perched at an average altitude of 665 meters, its steep, winding path mimics the shape of two crouching tigers—an apt description for terrain that blends rugged challenge with awe-inspiring views. For hikers seeking an authentic “wild Great Wall” experience, this route offers a glimpse into the structure’s unpolished, centuries-old charm.

Route Overview: Terrain & Key Details

Wohushan Great Wall stands directly opposite Panlongshan Great Wall, with the Beijing-Chengde Expressway dividing the two peaks. Unlike restored sections like Badaling, Wohushan has remained largely untouched for hundreds of years—most of its brickwork is deteriorated, with fragments scattered across uneven ground, and some stretches are too damaged to walk on. This is not a trail for beginners: only experienced hikers, ideally with a local guide, should attempt it, as navigating the broken paths and steep slopes requires caution.

The hiking route covers approximately 3 kilometers (1.8 miles) and takes 3–4 hours to complete, with the final ascent leading to Wohushan’s highest point at 705 meters. Along the way, you’ll pass 5 weathered watchtowers—each a relic of the wall’s defensive past, with crumbling interiors and overgrown ramparts that speak to centuries of wind and rain.

Hiking Experience: From Start to Summit

Your journey typically begins near the base of Wohushan, where a narrow dirt trail leads up to the first section of the wall. The initial climb is gentle, but soon the terrain steepens: you’ll step over loose bricks, grip gnarled tree roots for balance, and navigate slopes that often feel like climbing a natural staircase. This is not a route for casual strolling—every step demands focus, especially on sections where the wall’s original brick surface has eroded into bare earth.

After reaching the first watchtower, the path becomes more dynamic. Each subsequent tower (5 in total) serves as a small checkpoint and a chance to catch your breath. Inside these towers, you’ll find traces of the past: faint carvings on stone walls, and views that expand with every upward step. By the time you reach the 5th tower, the worst of the climbing is behind you—but the best reward lies ahead.

The final push to Wohushan’s 705-meter summit is worth the effort. From the top, a panoramic view unfolds: to the north, the mountains beyond the Great Wall stretch endlessly, their ridges blending into the horizon; to the south, inside the wall, Gubeikou Basin sits nestled among hills, with a small stream winding through its valley toward the distance. On clear days, you can even spot the outline of Panlongshan Great Wall across the expressway—creating a vivid picture of how these two peaks once worked together as a defensive barrier.

Practical Tips for Hikers

- Guide is a Must: Given the trail’s roughness and lack of signage, hire an experienced local guide (¥200–300 per group) to avoid getting lost. Guides also share stories about Wohushan’s history and point out safe paths through damaged sections.

- Gear Essentials: Wear sturdy hiking boots with strong grip (sneakers will slip on loose bricks), lightweight but durable clothing, and bring 2 liters of water (no water sources exist on the trail). Pack high-energy snacks like nuts or energy bars, and a small first-aid kit for minor scrapes.

- Best Time to Visit: Hike in spring (April–May) when wildflowers dot the slopes, or autumn (September–October) for cool weather and golden foliage. Avoid summer heat and winter ice—both make the trail dangerously slippery.

- Transport: From Beijing, take a high-speed train to Gubeikou Station (1.5 hours, ¥40), then a taxi to Wohushan’s trailhead (20 minutes, ¥30).

Wohushan Great Wall is not for those seeking comfort—but for hikers who crave authenticity, it’s a treasure. Every broken brick and steep climb tells a story of the wall’s resilience, and the summit views offer a perspective you won’t find at any restored section. This is the Great Wall as it has stood for centuries: wild, unyielding, and utterly magnificent.