For over 2,000 years, the Great Wall of China wasn’t just a stone barrier—it was a sophisticated, interconnected defense system designed to fend off northern nomadic tribes like the Mongols, Xiongnu, and Jurchen. Unlike modern fortifications that rely on technology, the Great Wall’s defense relied on clever engineering, strategic troop deployment, and simple yet effective tactics that turned a single wall into a “living” line of protection. Let’s break down how this massive structure kept ancient China safe, from its physical design to the soldiers who manned it.

1. The Wall Itself: Built to Block, Slow, and Observe

The Great Wall’s physical design was its first line of defense. It wasn’t just a tall wall—every detail was intentional, crafted to stop invaders in their tracks or make their advance so difficult that they’d retreat.

- Height and Width: Most sections stood 6–8 meters tall (taller than a two-story house) and 5–8 meters wide at the top. This made it nearly impossible for horses (the main mode of transport for nomadic armies) to climb over. Invaders would need ladders or ramps, which were easy to spot and destroy.

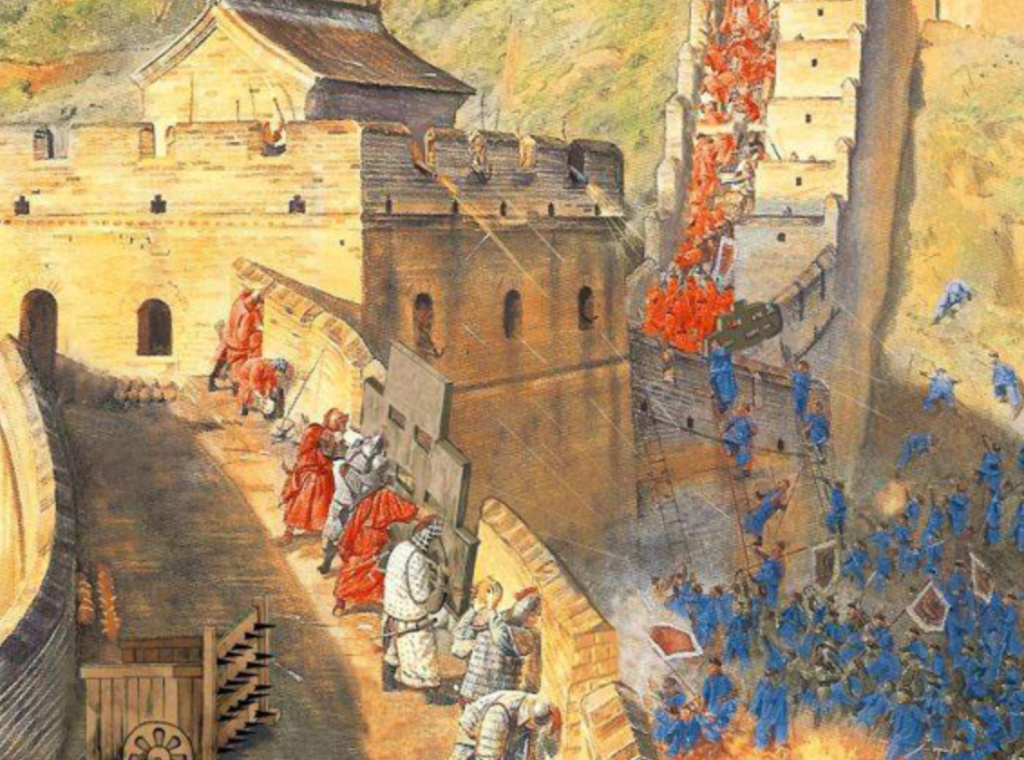

- Crenels and Parapets: The top of the wall had a low wall (parapet) on one side and notched gaps (crenels) on the other. Soldiers could hide behind the parapet for cover while using the crenels to shoot arrows, throw stones, or pour boiling liquids (like oil or water) down on attackers below.

- Moats and Barriers: In flat areas, many sections had a moat (a deep ditch) dug in front of the wall. Some moats were filled with water, while others were lined with sharp wooden stakes. These added an extra layer of difficulty—invaders had to cross the moat first, exposing themselves to attacks from above.

- Watchtowers: Every 200–500 meters along the wall, there were watchtowers (also called “beacon towers”). These stone or brick towers stood 10–15 meters tall, with windows facing north (toward potential threats). Soldiers in these towers kept a constant lookout for enemy movements, even at night.

2. Communication: The “Beacon Fire” System—Ancient China’s Early Warning Network

One of the Great Wall’s most brilliant defenses was its ability to send messages quickly across hundreds of kilometers. Before phones or radios, the wall used a “beacon fire” (fengsui) system to alert nearby garrisons of an attack.

Here’s how it worked: When soldiers in a watchtower spotted enemy forces, they’d light a fire on top of the tower. The fire was made with dry wood and wolf dung (which produced thick, black smoke that could be seen even in daylight). A second tower, within sight of the first, would see the smoke or flame and light its own fire—and so on, down the line.

This system was lightning-fast for its time. A message about an attack could travel 500 kilometers in just a few hours—fast enough for reinforcements to arrive before the invaders breached the wall. Sometimes, soldiers added extra signals: one fire meant a small raiding party, two fires meant a large army, and three fires meant an all-out invasion. This let commanders prepare the right number of troops and weapons.

3. Troops and Garrisons: The Soldiers Who Manned the Wall

The Great Wall’s defense wouldn’t have worked without the soldiers who lived and fought on it. During peak periods (like the Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644), up to 1 million soldiers were stationed along the wall at any time.

- Garrison Towns: Near key sections (like Badaling or Shanhaiguan), there were walled towns where soldiers lived with their families. These towns had barracks, training grounds, and storage rooms for food, weapons, and supplies. Soldiers rotated between patrolling the wall, guarding watchtowers, and training—so they were always ready for action.

- Weapons: Soldiers used a mix of long-range and close-range weapons. Long-range tools included bows and arrows (some with fire-tipped arrows to set enemy tents on fire) and crossbows (more powerful than bows, able to pierce armor). For close combat, they had swords, spears, and battle axes. Later, during the Ming Dynasty, they added early guns (called “fire lances”) and cannons to some watchtowers—game-changers that could take down groups of invaders at once.

- Patrols: Every day, small groups of soldiers (usually 4–6 men) patrolled the wall on foot or horseback. They checked for cracks in the wall, loose stones, or signs of enemy scouts (like footprints or broken branches). If they found something suspicious, they’d report back to their watchtower immediately.

4. Key Passes: The “Gates” That Controlled Access

The Great Wall wasn’t a continuous wall—there were gaps at mountain passes, rivers, and valleys. These gaps were turned into “strategic passes” (guan), heavily fortified areas that controlled all movement in and out of China.

The most famous pass is Shanhaiguan (the “First Pass Under Heaven”), located where the Great Wall meets the Bohai Sea. Shanhaiguan had a massive gate tower, multiple layers of walls, and a moat. It was guarded by thousands of soldiers and had storage rooms for enough food to last months. Invaders who tried to attack Shanhaiguan had to fight through multiple lines of defense—most gave up before even reaching the main gate.

Another important pass was Jiayuguan, in the Gobi Desert. It was the western end of the Ming Dynasty Great Wall and protected the Silk Road. Its design included a “barbican” (a small, enclosed area in front of the main gate) that trapped invaders—once they entered, soldiers could attack them from all sides.

5. Did It Always Work? Limitations and Real-World Challenges

The Great Wall’s defense system was impressive, but it wasn’t perfect. Sometimes, nomadic tribes found ways around it—by crossing frozen rivers in winter or sneaking through unguarded mountain trails. Other times, the wall fell because of political issues: if the Chinese empire was weak or short on soldiers, garrisons were understaffed, making the wall easier to breach.

But for most of its history, the Great Wall worked. It didn’t just stop invasions—it discouraged them. Nomadic tribes knew attacking the wall would mean losing time, soldiers, and supplies. More often than not, they chose to trade with China instead of fighting.

Why This Defense System Matters Today

Understanding how the Great Wall was defended isn’t just about ancient history—it’s about seeing the ingenuity of ancient Chinese military strategy. The wall’s defense system was one of the first examples of a “networked” defense, where every part (wall, watchtower, pass, soldier) worked together toward a single goal. Even today, military experts study its design to learn about early fortification tactics.

In the end, the Great Wall’s defense wasn’t just about stones and soldiers—it was about people working together to protect their homes, their culture, and their way of life. That’s why it’s more than a monument—it’s a testament to what communities can build when they need to defend what matters most.